This research article draws on in-depth interviews with Dr. Susanne Alldén, who is a senior lecturer in Peace and Development Studies at Linnaeus University in Sweden and has extensive field experience in conflict-affected regions, particularly in central and western Africa. She has also led and managed stabilization, peacebuilding, and gender equality programs in complex settings, including the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Burkina Faso, and Rwanda. Alice Viollet is another expert the article draws on, who is a Non-Resident Fellow at the Center on International Cooperation at NYU, and a former Program Officer working with the Congo Research Group team. She has also worked for the “Leading International Vaccinology Education” program funded by the European Commission’s Education, Audiovisual, and Culture Executive Agency.

Their insights help reveal the critical, yet often overlooked, roles Congolese women play in maintaining peace, managing crises, and rebuilding their societies during one of the world’s longest-running conflicts.

Background

The DRC has been plagued by protracted conflict for over three decades, keeping it on the Emergency Watchlist for over 10 years in a row as among the top 10 global crises. Since the DRC gained its independence from Belgian rule in 1960, the nation has experienced prolonged political turmoil and has struggled to establish a government capable of providing basic security to its people. The refugee crisis following the Rwandan Genocide intensified existing ethnic tensions in the country and led to Rwanda invading the DRC in 1996, backed by regional forces from Uganda. These incursions sparked the First and Second Congo Wars (1996-1997 and 1998-2003) — the latter often labeled as Africa’s World War. Since these wars, the Congolese people have faced recurrent attacks by armed groups, partly trying to exploit the DRC’s lack of state authority for access to rich minerals found in Congolese soil. Today, over 120 armed groups and militias operate in the eastern DRC.

After the end of the First and Second Congo Wars, the DRC experienced a period of fragile peace, although the conflict in the country has never been definitively over. The war was formally brought to a close with the 2003 Pretoria Agreement, which required Rwanda to withdraw its troops from eastern Congo. Although women’s influence in the Dialogue was constrained by the overwhelmingly male parties of armed groups, women formed a unified coalition that successfully increased the number of female delegates and lobbied for several gender provisions to be included in the agreement. However, many gender equality provisions stemming from the Dialogue remained largely unimplemented; women continued to be underrepresented in formal decision-making processes, and subsequent peace frameworks often remained insensitive to gender equality or disregarded lessons learned from previous efforts. The consequences of this failure to uphold these commitments are evident in the continued prevalence of sexual violence, limited access to justice for victims, and the continued exclusion of women from key peace negotiations.

Now, past conflicts have set the stage for today’s insecurity in the DRC. Since 2022, the conflict has entered a new phase with the resurgence of one particularly violent group backed by Rwanda: M23. Since the M23 armed group seized large swaths of eastern Congo, the DRC is facing an escalating humanitarian emergency. In particular, women and children face increased risks from M23 as conflict-related sexual violence, especially rape and abduction, is systemically used as a military strategy to terrorize communities.

Escalation of the Conflict (2022-Onwards)

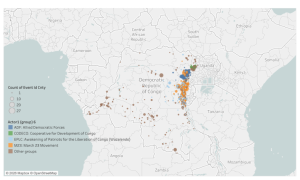

Since March 2022, the M23 insurgency in eastern DRC has escalated into a full-fledged regional offensive. The group began advancing into North Kivu, capturing the provincial capital of Goma, including its airport and government infrastructure, in January 2025. The M23, largely composed of Congolese Tutsi communities, articulates its rebellion around claims of political exclusion and protection for the rights of the minority group, security threats from rival armed groups, and unfulfilled provisions of previous peace agreements, while its operations are also driven by a desire for regional control and access to strategic economic resources. The map below depicts how fragmented the conflict landscape in the DRC has become, particularly between 2020 and 2025, with M23’s territorial concentration and escalation.

*Source: ACLED 2025

Meanwhile, the humanitarian cost has reached significant levels: according to the UN, the number of internally displaced people in North and South Kivu alone has surpassed 4.6 million since 2022, with new waves of displacement occurring as a result of the offensive in 2025. Furthermore, the offensive is linked to regional dynamics: Rwanda and Uganda have been involved through direct support for the insurgency, disputed mineral trade routes and infrastructure links, and competition over resource-rich mining areas currently controlled by M23.

Diplomatic and peacebuilding efforts have often struggled to cope with the rapid escalation of the conflict. Mediation initiatives led by Angola, the East African Community (EAC), and later the African Union (AU) aimed to secure ceasefire agreements and establish demilitarized zones. However, repeated violations and the M23’s rejection of terms have stalled progress. Moreover, the lack of an enforcement mechanism and regional rivalries have limited the effectiveness of these efforts and made a political solution to the conflict uncertain. As the conflict intensified, these dynamics disproportionally affected women and girls, setting the context for the gendered consequences outlined below.

Gendered Impact

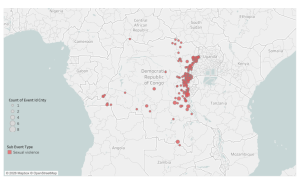

The escalation of the M23 insurgency since 2022 has had a gendered impact. As the group extended its territorial control in eastern regions, it became a leading cause of displacement: 71.4% of displaced women directly blamed the M23 for their displacement. When Goma and Bukavu came under M23 control in early 2025, reports of sexual violence increased. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights recorded a 270% increase in conflict-related sexual violence between January and February 2025 alone, while Amnesty International documented numerous cases of gang rape during and immediately after the attacks. This escalation also reflects a long-term pattern in which sexual violence is systematically used as a tactic of war by armed groups. One of the most striking examples is the Kishishe massacre in November 2022, in which at least 131 civilians, including women and children, were killed. Investigations have documented cases of sexual violence, mass killings, and targeted executions conducted by M23 fighters, describing the massacre as one of the deadliest incidents in the recent escalation. The map below shows a pattern of sexual violence in the DRC between 2020 and 2025, with eastern DRC as the epicenter and a regional spillover.

*Source: ACLED 2025

In displaced settings, where women and girls face multiple vulnerabilities, the humanitarian outcome has been critical. Humanitarian organizations have reported increased rates of sexual exploitation, forced prostitution, and abuse, with more than 124 brothels identified near camps in Goma alone. Women and girls were particularly vulnerable to sexual violence, including gang rape. Health workers interviewed by human rights organizations noted a significant increase in sexual and gender-based violence cases over the past two years, exceeding functional protective services.

The violence extends beyond the battlefield: the UN found that approximately 80% of women detained during the Makala prison escape had experienced sexual violence, demonstrating the persistence of gender-based harm in the DRC. Despite international and state protection policies, sexual and gender-based violence remains widespread and largely unpunished. Leading human rights observers report that women who go to the police to report sexual violence are often asked to pay for the procedures required to investigate and prosecute the crime. This situation reflects both the collapse of civil protection mechanisms in the country and the deep-rooted use of sexual violence as a tool of control and terror.

The gendered impact of conflict is also reflected in the loss of livelihoods and increased economic insecurity for women in conflict-affected areas. As communities are displaced from agricultural areas and trade routes are disrupted, women face significant income loss and increased food insecurity. In South Kivu alone, 67% of the households are severely food insecure and have poor food consumption levels. As a result, many women are forced into dangerous survival strategies, such as informal work, commercial sex, and unsafe migration routes, to support their families.

Health systems in conflict zones have simultaneously worsened, leaving women and girls with limited or no access to basic health services. Many camps lack sufficient access to maternal healthcare, contraception, or emergency care, forcing women to give birth in unsafe conditions without professional medical aid. On the other hand, attacks on health infrastructure, for instance, during the fighting in Goma, have resulted in numerous civilian casualties and extensive damage to civilian infrastructure. This breakdown of health systems further exacerbates the trauma of sexual violence, and victims face barriers to accessing post-sexual violence care, psychosocial support, and justice mechanisms. Taken together, these dynamics demonstrate how the armed conflict in eastern DRC is exacerbating pre-existing gender inequalities. However, women are making significant efforts to overcome these inequalities, improve their rights within the country, and participate in formal and informal peace processes.

Women’s Roles, Responses, and Agency in the Path to Peace

Women play an underrecognized but vital role in peacebuilding in the DRC. Despite being the targets of some of the most horrific conflict-related sexual violence in modern history, Congolese women are not merely victims but resilient agents of change, peacemakers, and healers.

Over the last three decades, women have been organizing to rebuild their communities from the ground up. In the words of Dr. Susanne Alldén, “Women represent the lived realities; they are the everyday peacemakers that keep fighting for peace every single day.” In the midst of the ongoing humanitarian emergency in the DRC, women are mobilizing to address immediate community needs through survival-driven initiatives, such as providing medical and psychological support to survivors of sexual violence and fighting against gender-based violence. Many of the local innovations in the DRC “blend livelihood support with advocacy,” according to expert Alice Viollet. For example, the Panzi Hospital and Foundation in Bukavu, DRC — founded by Dr. Denis Mukwege — has helped turn pain into advocacy by caring for over 87,000 survivors of sexual violence since 1999. In addition to providing physical help, the staff also provides legal, socioeconomic reintegration, and psychosocial services to patients while fiercely advocating against the atrocities of rape used as a weapon of war.

Civil society organizations (CSOs) are also key players in advancing gender equality and developing solidarity between women and girls in the DRC. Alice Viollet told us that, “From community reintegration and justice initiatives to advocacy and conflict prevention, women have led efforts that have measurably improved local security and social cohesion.” Institutions like local women’s coalitions, non-governmental organizations, human rights groups, and faith-based groups have increased their capacities and become better coordinated since the resurgence of M23. In 2023, the Ministry of Gender, Family, and Children of the DRC mapped the women’s movement across all of the country’s provinces, creating a shared database to bring together actors in the gender equality sector. This initiative, which connects 1050 women’s CSOs in the DRC, facilitates shared information and creates a synergy across the movement that amplifies Congolese women’s calls for equality and justice.

In formal peace processes, there have been positive strides of women moving out of the margins of peacebuilding and stepping into leadership roles as dispute-resolvers and mediators. Alice Viollet highlighted Bintou Keita, the UN Special Representative in the DRC, for advancing gender-sensitive peacebuilding at the national level in the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the DRC (MONUSCO). In October 2025, MONUSCO’s Gender Section organized meetings to promote women as full actors in peacebuilding under the theme of “When women lead, peace follows.” Furthermore, women who were once hidden from public life are being empowered and trained to manage tensions and resolve conflicts within their own communities. In particular, through an initiative by the Secretary-General’s Peacebuilding Fund (PBF), over 200 women in the Kasai Province are trained as community mediators to settle disputes before they become violent, such as land conflicts, family feuds, and inter-community tensions. Some of these female mediators have assumed leadership roles in political positions and the National Assembly. These female mediators are helping to defy stereotypes that historically keep them out of decision-making, laying the groundwork for a sustainable peace built on inclusion.

Despite the profound impact women are making in their communities, their direct participation in high-level peace initiatives remains limited. Formal peace frameworks and negotiations in the DRC remain a male-dominated sphere where women are largely excluded. Although the Congolese Constitution contains provisions regarding women’s right to equal participation in politics, women only occupy 7.2% of positions at the highest level of decision-making at the national level. According to Alice Viollet, current peace initiatives have fallen short at meaningfully integrating women’s voices, finding that their participation is largely tokenistic. She stated, “While public institutions and international partners frequently highlight women’s ‘inclusion,’ this inclusion is often symbolic: women are present, but rarely empowered to influence priorities, budgets, or outcomes.”

Women advocates in the DRC also have to overcome structural discrimination that continues to fuel these inequalities, such as impunity for perpetrators of sexual violence. Despite the mounting cases of sexual violence committed by combatants on all sides of the fighting in the DRC, most of the perpetrators of these war crimes are going unpunished. This absence of accountability for the survivors of these violations is protecting perpetrators while depriving women of justice and their human rights. Moreover, Congolese women fighting against gender inequality also face security risks when their voices are actively threatened and they become the first targets of oppression. Despite the courage and resilience of women in peacebuilding, women’s efforts — especially at the grassroots level — have limited visibility. As Dr. Alldén explained, “They are the silent peacemakers who rarely get recognized.”

Policy Recommendations

Strengthening Health Systems and Essential Services

The Congolese health system is deteriorating, with M23 clashes destroying medical facilities, overwhelmed hospitals, and leading to disease outbreaks. Emergency response efforts are crucial to address the gap between the intensifying health crisis and available aid. The DRC has among the highest rates of maternal and neonatal deaths in the world, underscoring the need to support local centers that can provide more specialized care and monitoring of women with high-risk pregnancies. Access to healthcare in the DRC also needs to be improved through the rebuilding of destroyed infrastructure and increased training of healthcare personnel. Investing in WASH (water, sanitation, and hygiene) infrastructure to prevent the spread of cholera, measles, and mpox is also critical.

Since the M23 resurgence, there has been an unprecedented number of sexual violence cases, calling for a scaling up in medical assistance for these victims. According to Christopher Mambula, the head of Doctors Without Borders Programs in the DRC, “The few programs that do exist are always too short-lived and grossly under-resourced. Much more is needed to protect women and meet the urgent needs of victims.” To respond to the needs of survivors of sexual violence, there must be increased access to basic needs and services that focus on holistic care. These programs must integrate high-quality physical treatment with medical, psychosocial, legal, and socio-economic care as well.

Supporting Women’s Leadership and Capacity

As Alice Viollet noted, Congolese “women have long led efforts that have measurably improved local security and social cohesion through community reintegration, justice initiatives, advocacy, and conflict prevention.” Some women-led initiatives include Balobaki, The Panzi Foundation, Synergie des Femmes pour les Victimes des Violences Sexuelles (SFVS), or the Global Survivors Fund. “They use everyday community spaces (markets, schools, churches, etc.) as neutral grounds for dialogue, negotiation, and protection.” Women’s initiatives continue to grow and develop, “proving that sustainable peace in the DRC is impossible without women’s leadership and inclusion.”

Therefore, policies that support women’s participation are crucial. In this regard, institutional efforts such as gender quotas are central mechanisms for promoting equality and women’s representation. “Quotas should not only mandate women’s representation in peace processes, political institutions, and local governance, but also extend to funding distribution.” Ultimately, while quotas are essential, sustained efforts are also needed to transform the social and institutional norms that continue to exclude women’s voices.

Transforming Institutional Norms

Despite the existence of legal frameworks that support gender equality, rooted patriarchal traditions and informal power networks often exclude women’s voices from party structures, peace negotiations, and economic recovery initiatives. Alice Viollet also emphasizes that “while public institutions and international partners frequently highlight women’s “inclusion,” this inclusion is often symbolic: women are present, but rarely empowered to influence priorities, budgets, or outcomes.” Therefore, institutional reforms should prioritize leadership and accountability tools that promote equal decision-making and uphold gender equality. As Dr. Alldén suggests, “Every negotiation team, including a ceasefire or a peace committee, local peace structures, and similar, should have a mandatory women representation of a minimum 40%.” So, sustainable peace and women’s equal and active participation in decision-making and peace-making at the community and national levels are crucial for translating these transformations into a lasting culture.

Challenging Social Stigmas and Narratives

Women “are mostly portrayed as passive victims, but they are the force behind most local and everyday peace action taken,” notes Dr. Alldén. However, ingrained social stigmas and gender narratives continue to limit women’s participation in the political, peacebuilding, and economic spheres in the DRC. Deep-seated beliefs about women’s roles and responsibilities often position them as secondary actors, hinder their leadership, and silence their voices in public life. Challenging these stigmas requires public awareness campaigns highlighting women’s contributions to governance and peacebuilding, educational restructuring, and media participation that shapes public discourse around women’s roles and leadership. Partnerships with community leaders, faith-based organizations, and youth groups can also help fundamentally reshape attitudes. Therefore, “there needs to be national and local ownership and commitment” to make such a change sustainable.

Conclusion

Taken together, these insights reveal that women in the DRC are not merely victims of conflict but also key builders of peace. Ensuring their participation in peace processes and society through stronger institutions, equitable policies, and improved social norms should not only be a gender objective but also a prerequisite for a lasting and just peace. The path forward depends on recognizing women’s leadership, addressing the systemic violence they face, and investing in structures that will enable their voices to shape the DRC’s future.