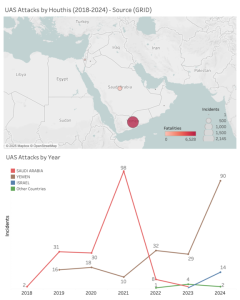

The Houthi movement, designated by the U.S. as a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO), has emerged as the most prolific violent non-state actor employing Unmanned Aerial Systems (UAS). According to GTTAC data, the group has conducted 388 drone attacks from 2018 to 2024, targeting a wide array of actors, including the Yemeni government, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Israel, U.S. military forces, and international commercial and naval vessels in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden (see Figure 1). As a sanctioned non-state actor with restrictions in accessing military-grade and dual-use technologies, the Houthis’ sustained and increasingly sophisticated drone operations raise a pressing question: how do they adapt UAS capabilities at this scale? Drawing on publicly available information on documented interdictions and forensic analysis of recovered systems and the existing literature, this report investigates the commercial and state-oriented mechanisms through which the Houthis acquire UAS technology.

Figure 1. Dashboard of UAS attacks by Houthis from 2018 to 2024 (Source: GRID)

The first Houthi deployments of drones were in their domestic conflicts, primarily in strikes against the internationally recognized government of Yemen and its foreign backers, a coalition led by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. The strikes were sporadic, and mainly targeted critical infrastructure. While only 29 incidents were recorded in the years preceding Hamas’s October 7th attack on Israel, the year following October 7 saw the frequency of Houthi attacks significantly increase as they formally declared war on Israel in their capacity as a member of “axis of resistance.” Despite more than 1,300 miles separating Yemen and Israel, seven distinct UAS attacks were launched at Israel itself, with one successfully breaking through Israeli air defense. A larger volume of attacks, however, targeted shipping in the Red Sea. These Houthi attacks led to significant disruption of world trade, as over 12% of global exchange was threatened from both missiles and drones, impacting ships from over 65 countries. Among 89 Houthi UAS attacks, 52 targeted US naval vessels. However, none of these 52 drones hit their intended naval targets due to the effectiveness of counter-drone technologies. While these attacks were not able to provide the expected physical destruction of the targets, they demonstrate an unbalanced financial situation. According to the US Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment William LaPlante, “If we’re shooting down a $50,000 one-way drone with a $3 million missile, that’s not a good cost equation.”

Clearly, UAS technology allows the Houthis to expand their operational reach beyond the Arabian Peninsula, making them one of Iran’s most effective and threatening regional proxies. While the Houthis claim internal design and manufacture of their UASs, there is clear evidence that many of the components for Houthi drone technology originate in Iran, which are then smuggled piecemeal into Yemen and assembled by the Houthis. The Houthis have also shown themselves to be increasingly resourceful both in manufacturing specific components of drones in Yemen and sourcing advanced parts from third-party civilian sources outside of Iran. For a more nuanced investigation, this paper goes through each type of drone on a case-by-case basis.

Types and Sources of Drone Technology

Commercial Market

One source of Houthi drone technology stems from modifications of commercially available civilian drones. Houthi Rujum drones, for example, are adaptations of Chinese hexacopter drones made by companies such as DJI. These multi-use drones have a short range of only 10 to 30 kilometers, but can be adapted to drop payloads over their targets before returning intact. Due to their short range, they are most effective in Houthi domestic operations, serving as a low-cost method for sustaining offensives on the ground.

Figure 2. Rujum Drones (Image Source: Oryx)

| Drone Type | Rujum |

| Iranian Counterpart | N/A |

| Length | Varies |

| Wingspan | Varies |

| Armed? | Yes, typically with six mortar grenades which can be dropped on a target with precision. |

| Range | 10-30 Kilometers |

| Evidence of Domestic Houthi Assembly? | N/A |

| Available on Civilian Market? | Yes. Identical to Chinese Quadcopter Drones produced by DJI. |

Houthi Rased, or, “surveyor” drones, are also adapted from civilian uses, as they are identical to the Chinese X-8 Skywalker drone, which can be purchased online. Rased drones, with a small airframe, have a range of around 35 kilometers and are used primarily for reconnaissance. While these two civilian drone adaptations have limited range, their use on domestic frontlines has proven effective.

Figure 3. Rased Drones (Image Source: ODIN)

| Drone Type | Rased |

| Iranian Counterpart | N/A |

| Length | 1 Meter |

| Wingspan | 2.2 Meters |

| Armed? | Usually used for Reconnaissance |

| Range | 35 Kilometers |

| Evidence of Domestic Houthi Assembly? | N/A |

| Available on Civilian Market? | Yes. Identical to Chinese Skywalker X-8. |

As these drones are adapted from civilian uses, Houthis have been able to acquire them through online sources. For the Rased specifically, the UN Panel of Experts noted over 10 websites where the Skywalker X-8 can be purchased with a simple online transaction, ranging from specialty UAS companies to websites such as E-Bay. These websites do not require any sort of security verification, and if the company would not ship directly to Yemen, a quick search confirmed that “forwarding services” could be used to ship from third-party retailers into Sana’a itself. Indeed, from November 2022 to June 2023, the Internationally Recognized Government (IRG) of Yemen intercepted 254 UASs entering the county from various sea and land routes. One such shipment, on March 12, 2023, was of 54 quadcopter UASs (similar to the Rujum) moving across the Shahn border crossing from Oman. Prior to that, 200 civilian drones of an unspecified brand were seized in the port of Aden, each equipped with a surveillance camera. Despite Houthi claims of domestic manufacture, these Rased and Rujum drones are of civilian origin, and then acquired possibly through online sources. Another possibility, especially considering these drones were captured alongside other weaponry, is that the civilian drones were purchased by Iran and summarily smuggled into Yemen.

Military Grade UAS: Qasef

Aside from adapted civilian drones, the Houthis also employ military grade “kamikaze” drones. Qasef drones, one of the earliest Houthi additions to their UAS arsenal, have an Iranian-designed counterpart, the Ababil-T, and sport wingspans over 3.25 meters and a range of around 120 kilometers. These drones are capable of wielding 30-kilogram warheads, which are used in effective one-way attacks on adversaries. This renders the Qasef drone ideal for attacking fixed targets deep behind the frontlines. One such attack by the Houthis was in 2018, as a Qasef drone attacked a Saudi Coalition Patriot anti-missile system. Later that year, a Qasef was used in attacks on Saudi critical infrastructure, including a Saudi Aramco oil facility and a civilian airport.

When evaluating the technologies present in Qasef drones, and tracking their sources, many indications point to Iranian origin. In 2018, soldiers from the UAE were able to capture several Qasef drones mostly intact. These drones were found to have matching serial numbers on the fuselage and interior components, perhaps etched by Iranians to make facilitate easier assembly in Yemen. One such internal component found in the captured Qasefs, the Vertical V-10 Gyroscope, is identical to a Gyroscope discovered in a downed Iranian-manufactured drone in South Sudan. Many of the components of the captured Qasefs are also found in IEDs deployed by Iranian-backed Bahraini militant factions, including quality control stickers and microcontrollers. Several parts, including heat-shrink sleeving, are identical to equipment that was intercepted on the merchant vessel Jihan 1 in 2013 as it smuggled weapons from Iran to the Houthis. Another traceable Iranian shipment of components to the Houthis occurred in 2016. According to a 2018 UN document, a Dubai-registered truck intercepted near Ma’rib in Yemen was found carrying the components for at least six fully assembled Qasef-1 drones, technologically identical to the Ababil-T, as well as the parts sufficient to produce an additional 24 units. This case strongly indicates Iran’s complicity in supplying both the designs and components of Qasef drones to the Houthis.

However, not all components of the Qasef drones originate directly from Iran. In 2018, a different drone captured by the UAE was a “hybrid” drone, with similar internal components as the assembly line Qasef drones. The difference, however, is in the airframe. Unlike the standard models, the hybrid Qasef’s airframe was “poorly constructed” out of fiberglass and was likely manufactured locally in Yemen. Given that fixed-wing-drone airframes span several meters both in length and width, smuggling them in large quantities presents logistical challenges. It is therefore plausible that the Houthis may have attempted to produce their own airframes in order to save costs or simply out of necessity in the face of shortages.

Figure 4. Qasef Drones (Image Source: ODIN)

| Drone Type | Qasef |

| Iranian Counterpart | Ababil-T |

| Length | 2.88 Meters |

| Wingspan | 3.25 Meters |

| Armed? | Yes- 30 kg warhead |

| Range | 120 Kilometers |

| Evidence of Domestic Houthi Assembly? | Yes, with components sourced independently from Iran |

| Available on Civilian Market? | Not in entirety, only in certain components |

Military Grade UAS: Sammad

Sammad drones, more specifically the Sammad 3 variation, are a more recent addition to the Houthi arsenal compared to the earlier Qasef models. Like the Qasef UASs, Sammad drones have components of Iranian design and supply. With their distinctive “V-Style tails,” flight control surfaces and slender fuselage, the Sammad closely resembles the Iranian Sayad UAS. While similar in size, the major advantage that the Sammad holds over the Qasef is its range. The Sammad 3, which is fitted with fuel tanks for increased range, can reach up to 1500 kilometers while carrying a warhead. This only amplifies any tactical advantage, as the Houthis have the capacity to expand their reach and hit targets far beyond even the Arabian peninsula. For instance, the Sammad 3 drone was used in a successful long-range attack on Tel Aviv in 2024. Despite these clear advantages in range, the Sammad 3 has the drawback of being exceptionally inaccurate, as it is described frequently as “inexpensive, small, slow and clumsy.”

A Sammad drone was also captured in 2018 by the UAE, allowing for a detailed inspection of its internal components. Many of its components were similar to those found in the Qasef drone, such as the heat shrink sleeving or voltage regulator, both of which are of Iranian origin. However, the engine of the captured Sammad 3 was a point of interest, as it was a German-manufactured 3W-110i B2 engine. The engine markings on the captured drone were ground off by the Houthis. A UN Panel of Experts, however, was able to track the engine to a consignment sale in 2015. The engine was exported from Germany to Greece, then from Greece to Turkey. At that point, the engine was sold to Giti Reslan Kala, a logistics company, who passed it to Tafe Gostar Atlas in Tehran. Presumably, the engine was then smuggled into Yemen. This complex supply chain illustrates the problems associated with trying to crack down on arms smuggling. Since the 3W-110i B2 is described by its manufacturer as an engine suited for “towing, acrobatics, or scale models” (a quick search on YouTube confirmed that this means model airplanes), it would not necessarily be flagged by any of the intermediaries or customs officials along the supply chain as particularly concerning. They are only looking for arms transfers to Yemen. As the UN Panel indicates, this “hampers the Panel’s investigative efforts and assists the Houthi war efforts.”

The smuggling of engines for the Sammad through third party sources persists with the Chinese DLE-170. On December 31, 2022, a truck crossing the border from Oman was captured by Yemeni government officials. Inside were 100 DLE-170 engines, identical to ones found on Sammad 3 drones publicly displayed by the Houthis. The DLE-170s, similarly to the German engines, are listed by the manufacturer as being used exclusively for Radio Controlled model airplanes.

It is not only engines, however, that the Houthis are able to smuggle into Yemen from foreign civilian manufacturers. In 2019, Saudi Coalition forces captured almost 3 tons of UAS parts in the Jawf region that had been shipped from Oman. Aside from the usual complement of DLE-170 engines, the shipment also contained exhausts, electronic ignition boxes, and a large quantity of propellers, which are used in both Sammad and Qasef drones. While there were no shipping labels, the shipment was tracked to Hong Kong, China. An entity (possibly an individual or a front company) named Bahjat Alleqa’a, based in Oman, picked up the cargo at Muscat International Airport. As before, an intermediary was used to facilitate the transfer of ostensibly civilian manufactured goods.

In November 2018, 60 SSPS-105 servoactuators were exported from Japan to Abu Dhabi by a man named Saleh Mohsen Saed Saleh. His telephone number is known to be associated with a company named Al-Bairaq, specializing in international land transport between the UAE and Yemen. The intended recipient was a Yemeni man named Mohammed al-Swari, a known specialist in UAS components. While these servoactuators never arrived in Yemen, it is still remarkable in showing the complex chain of intermediaries these civilian components are routed through before arriving in Yemen and being assembled into military UASs.

The Houthi ability to source a wide range of components for their Sammad and Qasef drones from civilian manufacturers abroad, partially independently of Iranian supply chains, is notable. As the UN Panel of Experts concluded in its comprehensive 2020 report, “uncrewed aerial vehicles belonging to the Qasef and [Sammad] families are manufactured inside Houthi-held territory using a mix of locally available materials (e.g., fibreglass for the fuselage and wings) and high-value components sourced from abroad.”

Figure 5. Sammad 3 Drones (Image Source: ODIN)

| Drone Type | Sammad 3 |

| Iranian Counterpart | Sayad |

| Length | 2.8 Meters |

| Wingspan | 4.5 Meters |

| Armed? | Yes |

| Range | 1500 Kilometers |

| Evidence of Domestic Houthi Assembly? | Yes, with components sourced independently from Iran |

| Available on Civilian Market? | Not in entirety, only in certain components |

Military Grade UAS: Waid

As we have seen, the Qasef and Sammad drone systems are influenced by Iranian designs, and most likely assembled in Yemen using the equipment smuggled directly from Iran or (increasingly) from difficult to trace third-party civilian sources. However, the Waid 2 drones, used most frequently against shipping in the Red Sea, require advanced engines, radar-resistant airframes, and targeting systems that are difficult to obtain on the open market, much less produce in Yemen. The Waid 2 has a range of over 2000 kilometers, and can carry a 40-kilogram warhead for use against merchant shipping or foreign naval assets. The Waid 2 is commonly known as a “loitering munition,” as it can hover over a designated target area for hours before descending to its target. Its attack angle is low to the water, where civilian radar cannot pick it up. Clearly, this is a more advanced “kamikaze” UAS than the Qasef or Sammad. While less concrete evidence exists about shipment of Waid parts to Yemen from Iran, it is not beyond the scope of imagination that this is possible. According to imagery obtained by the US Defense Intelligence Agency, the Waid 2 is similar to the Iranian-built Shahed 136 drone in all of its outward facing components, including identical wing stabilizers, nose cones (used to deliver payloads), pitot tubes, and a slender fuselage.

Interestingly, the design is also identical to the Russian Geran-2 UAS, which is one of the most common weapons in the Russian drone fleet and is regularly used against targets in Ukraine. It is this connection between Iran and Russia for Shahed 136 manufacture that convinces experts into thinking that Iran would be able to do the same for the Houthis. According to David Kovar, an expert on drone forensics, because “Russia [has] been forced to develop these ‘just in time’ supply chains for all of the various components they need for drones, those supply chains exist for other people to leverage them. And so, if Iran is working with Russia, then that supply chain most likely is also available to the Houthis.” Since a Geran-2 is estimated to cost the Russians only around $35,000 to assemble, and assuming the Houthis may be able to tap into these same supply lines, even the most advanced Houthi drones could be inexpensive if they are assembled in Yemen. This domestic assembly, too, is plausible. A senior US defense official, in an interview with TWZ, indicated that the US military believes much of the Houthi assembly of drones is done “in-house.” If the Houthis are able to assemble the lower-cost drones in Yemen, logic holds that they would be able to assemble the Waid 2s, as well.

Figure 6. Waid 2 Drones (Image Source: ODIN)

| Drone Type | Waid 2 |

| Iranian Counterpart | Shahed-136 |

| Length | 3.5 Meters |

| Wingspan | 2.5 Meters |

| Armed? | Yes- 40 kg warhead |

| Range | 2000 Kilometers |

| Evidence of Domestic Houthi Assembly? | No hard proof, but likely |

| Available on Civilian Market? | No. Parts likely sourced from Iran. |

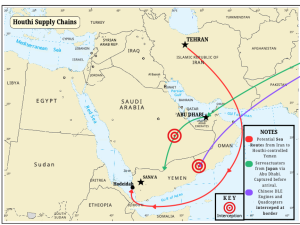

Routes of Houthi Supply Chains

Up to this point, this report has referenced several routes regarding how both civilian and military grade drones enter Houthi-controlled Yemen. A more structured summary of these supply routes would perhaps be beneficial. One method of transport into Yemen is through land routes. Take, for instance, the aforementioned 2022 capture of 100 DLE Engines or 2023 capture of 54 civilian quadcopter drones at the Shahn border crossing from Oman. In 2019, the servoactuators from Japan were seized before entry into Yemen, but were intended to be smuggled by a company called Al-Bairaq, specializing in international land transport between the UAE and Yemen.

What is much more difficult to track, however, is the exact number of Iranian shipments into Yemen by sea. Between 2015 and 2024, the United States and her allies interdicted at least 20 Iranian vessels headed to supply the Houthis, several containing the components for UAS construction. In one such interdiction, a United States vessel discovered almost 200 packages containing an assortment of weapons—from ballistic missiles to uncrewed vehicle technology. This interception was legal as any supply of weaponry to Yemen violates U.N Security Council resolution 2216. However, whatever limited captures the United States or its allies conduct do not indicate the true scale of weaponry arriving into Houthi controlled ports that are not inspected by any outside power. The British government found that the Houthi port of Hodeidah was serviced by over 500 unsearched ships during eight months of 2024, many of which could have contained weapons or drone components. According to the Wilson Center, the Iranian Quds force utilizes small dhows to smuggle weapons, taking great care to avoid U.S. patrols around the Horn of Africa and Gulf of Aden.

Figure 7. Map of Houthi Supply Chains (Base Map of Western Asia Source: United Nations)

Potential for Technological Advancements

Technology advancements will only amplify the threat that drones can pose, and perhaps even lower the already low costs of Houthi domestic production. In February 2025, a shipment en-route to the Houthis was captured containing jet engine technology and first-person view (FPV) systems. The jets were unique in the sense that they were too small for cruise missiles, and had never been documented as moving into Yemen before. If equipped with jet engine technology, the drones would be able to travel up to four times as fast, combining the low cost of a drone with the speed of a missile. The FPV technology would allow for drones to be actively manned by an operator, which would be essential for more accurate tactical strikes.

Perhaps the most transformative innovation would be the adoption of 3D printing. If the Houthis were able to 3D print the airframes of the drones, further reducing their need for Iranian imports, they could become more self-reliant. 3D printing, besides allowing cheap production of airframes or other essential components, does not require particularly skilled labor in production, and can be modified to fit the need of any drone. The transfer of 3D printing technology would be difficult to stop, as well, due to uses which are largely legitimate.

Another potential technology with major implications is Artificial Intelligence (AI). While AI is extensively used by militaries, the adoption of AI in Houthi systems could dramatically increase their effectiveness in combat. For example, AI could be used for image-based navigation, rendering it impregnable to GPS jamming. As the Houthis adapt these existing technologies into their drones, their effectiveness both in combat and in ease of domestic manufacturing will potentially increase.

Conclusion

Houthi drones, which in recent years have expanded the group’s operations from domestic to regional conflicts, are sourced from a variety of sources and transported into their territory through both land and sea. The group’s ability to combine Iranian state support with commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) technology and decentralized supply chains exposes critical gaps in supply control mechanisms. This report reveals that current counter-proliferation and arms interdiction strategies have been insufficient to curtail the Houthi movement’s rapidly advancing drone capabilities.

Addressing this challenge requires a broader and more adaptive approach. It is not sufficient to interdict readymade weapon systems or focus solely on shipments from Iran. Instead, the U.S and its allies must expand their imagination of what common parts and technologies might be repurposed for military uses, and recognize the variety of potential sources for such material beyond Iran since many of the key components used in Houthi drones such as gyroscopes, servoactuators, ignition systems, and small aircraft engines are available on global civilian markets and often shipped through complex intermediaries. To mitigate the transfer of dual-use civilian technology, manufacturing countries should enhance end-use verification, transaction screening algorithms, and mandatory tracking of high-risk UAS components.

In addition, logistics firms and front companies in countries like Oman, the UAE, Turkey, and Hong Kong serve as intermediaries in drone part transfers. The U.S and its allies should expand sanction mechanisms on front companies and logistics networks by targeted financial sanctions and corporate blacklisting to reduce loopholes in maritime and land-based smuggling routes. Despite multiple documented interdictions, land crossings and maritime routes from Oman, the UAE, and Iran remain active channels for drone component delivery. More robust maritime inspection regimes, such as enhanced patrolling around the Horn of Africa and coordinated enforcement of UN Security Council Resolution 2216, are necessary.

Houthi extremists have evolved into a drone-capable non-state actor with regional reach, growing operational sophistication, and stand-off strike capabilities. An effective response must go beyond reactive counter-drone technologies and enhance coordinated efforts across intelligence, regulatory frameworks, and industry collaboration to disrupt the Houthis’ multifaceted drone supply chain.