Haiti is on the verge of a total institutional collapse, with only 10% of the capital in control of the Haitian government—a government entrenched with corruption.[i] Instead, Haitian gangs are nearing total control of the capital and Haitian authorities can no longer combat the escalating violence.[ii] The current crisis goes beyond a scourge of gang violence as the gangs operate in parallel to the state, enabled by political instability, corruption, and weak institutions.[iii] Yet, international efforts have found little success in defining the reasons behind the current crises, which only further contributes to an inability to find an effective response. The U.S., and other international partners, need to recognize that an effective response does not involve sweeping political reform, but instead must focus on supporting local level security, access to humanitarian aid, and regional cooperation.

When I first visited Haiti in 2019 with Parakaleo International, we flew into Port-au-Prince and were able to drive through the capital to Jacmel without issue. However, by the time I traveled to Haiti in January 2021, security issues had escalated to the extent that we could no longer safely travel through the capital and instead had to fly in a private plane to Jacmel, only a fifteen-minute flight.

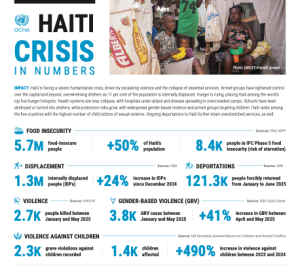

The assassination of President Moïse in July 2021 plunged the country into further turmoil, evolving into a full-scale security and humanitarian disaster.[i] Violent gangs have not only amassed control over most of the capital, but over illicit markets.[ii] In 2024 alone, gang violence contributed to the killing of more than 5,600 people.[iii] In addition, 5.4 million Haitians face acute food insecurity, with 1.64 million of those in emergency levels.[iv] Gangs have shut down hospitals or rendered them unusable, blocked roads, and imposed illegal taxes.[v] The below graphic shows a representation of the crisis as of June 2025.

These challenges have been further compounded by a history of vulnerability to natural disasters. Most notably, in 2008, the country was hit by four hurricanes, decimating agriculture and infrastructure critical to public health, education, and business. Then, in 2010, the country was hit by a 7.0 magnitude earthquake that directly impacted Port-au-Prince.[i] As a result, vital infrastructure remains fragile or nonexistent, with little hope of rebuilding.

The United States has long played a critical role in Haiti’s political and security landscape. Since the early 1900’s, there have been at least three direct interventions in Haiti, including a long stint of occupation by U.S. forces from 1915 to 1934.[i] While the U.S. and other international partners have continually intervened with rebuilding and responding to the ongoing humanitarian crisis, there has seemingly been little impact. In 2024, a Kenya-led, UN-authorized Multinational Security Support (MSS) Mission, that the U.S. helped to train and equip, was deployed. Yet in 2025, the security and political situation in Haiti has continued to deteriorate, with 2,700 killings between January and May alone.[ii] While the Biden administration sought to support Haiti by helping fund the MSS to address gang violence and promote security, more needs to be done.

However, because so many interventions by international partners have been unsuccessful, there is a hesitancy among U.S. politicians to lead a new international mission to Haiti. Yet, the Haitian government is in disarray, violence is rampant, and people are beyond starving.[iii] One of the foremost human rights defenders in Haiti, Pierre Esperance, said that Haiti needs “a functional government. An international force will not be able to solve the problem of political instability. At the same time, Haiti cannot wait. We are in hell”.[iv] OCHA’s country director for Haiti told the United Nations that “the rise of armed groups in Haiti and their increasing control of strategic locations, particularly major roads and ports of entry into the capital, is a major obstacle to the safe and efficient delivery of humanitarian aid”.[v] Long-term stability in Haiti has never been achieved without security and security has never been achieved without international intervention.[vi]

The current crises plaguing Haiti offer an opportunity for the U.S. to reconsider its approach to interventions in Haiti. While past interventions offer lessons about the risks of overreach, the consequence of ignoring the present situation encourages a continued humanitarian crisis that worsens with each passing day. Where violence carried out by theses criminal organizations was once primarily within the capital, they are now spreading beyond the capital, where they “kill, rape, set fire to homes, and infiltrate all spheres of society”, with over a million citizens now displaced.[vii]

High-level policy reforms will continue to fail if they are not grounded in the reality of the current state of Haiti. First and foremost, little can be achieved without an improved security situation. The absence of security, functional infrastructure, and a cohesive local government have made it nearly impossible to distribute foreign aid. Criminal groups control key roads and ports and reaching those in need is nearly impossible without increased security and trusted local actors. Therefore, effective policy must first focus on rebuilding foundational systems that allow aid, safety, and governance to take root.

Recommendations

Haiti’s security and humanitarian crisis poses a difficult challenge with both regional and global implications. Years of political instability and heightened security issues, made worse by natural disasters, have eroded the country’s institutions and displaced millions. Previous interventions by the U.S. and international partners, while well-intentioned, have struggled to address the root causes of the issues. For the U.S., the consequences of inaction are clear: escalating violence, regional destabilization, and a worsening humanitarian crisis. By prioritizing local-level security, ensuring effective and transparent aid delivery, and expanding protections for vulnerable Haitian children, the U.S. can help create the conditions necessary for stability and growth.

[i] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/3/14/what-is-the-history-of-foreign-interventions-in-haiti

[ii] https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/haiti/haiti-crisis-numbers-25-june-2025

[iii] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/3/14/what-is-the-history-of-foreign-interventions-in-haiti

[iv] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2024/3/14/what-is-the-history-of-foreign-interventions-in-haiti; https://www.congress.gov/116/meeting/house/110326/witnesses/HMTG-116-FA07-Bio-EspranceP-20191210.pdf

[v] https://news.un.org/en/story/2025/07/1165533

[vi] https://www.stimson.org/2024/rethinking-the-international-response-to-haitis-security-crisis/; https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/feb/02/the-world-at-war-the-flashpoints-that-the-west-ignores

[vii] https://news.un.org/en/story/2025/03/1161006

[viii] https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IN12331

[ix] https://cepr.net/publications/a-look-at-usaid-spending-in-haiti/

[x] https://www.nrc.no/globalassets/pdf/reports/protection-of-civilians-and-access/nrc-corridors-explainer.pdf

[xi] https://www.nrc.no/globalassets/pdf/reports/protection-of-civilians-and-access/nrc-corridors-explainer.pdf

[xii] https://ht.usembassy.gov/u-s-citizen-services/child-family-matters/adoption/

[xiii] https://ht.usembassy.gov/u-s-citizen-services/child-family-matters/adoption/

[xiv] https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/News/Intercountry-Adoption-News/the-department-of-state-advises-prospective-adoptive-parents-to-0.html

[xv] https://www.latimes.com/world-nation/story/2023-06-13/30-000-haitian-kids-live-in-private-orphanages-officials-want-to-shutter-them-and-reunite-families#:~:text=Roughly%2030%2C000%20children%20out%20of,trafficking%2C%20forced%20labor%20and%20abuse.

[xvi] https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/humanitarian_parole

[i] https://www.unops.org/news-and-stories/stories/building-a-resilient-haiti

[i] https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-57762246

[ii] https://www.congress.gov/crs-product/IN12331

[iii] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2667193X25000754

[iv] https://www.actioncontrelafaim.org/en/press/violence-in-haiti-drives-nearly-5-million-people-into-hunger-crisis/

[v] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2667193X25000754#bib3

[i] https://www.hrw.org/news/2025/06/30/haiti-on-the-edge-of-collapse; https://international.ucla.edu/institute/article/285803

[ii] https://apnews.com/article/un-haiti-gangs-capital-violence-government-kenya-c14dd55725e2e415b794ab88b4184e65

[iii] https://warontherocks.com/2025/04/haiti-is-a-political-and-criminal-crisis-that-should-not-be-ignored/