Introduction

In October 2025, cross-border conflict surged between Afghanistan and Pakistan over allegations of terrorist safe havens in Afghanistan and drone strikes carried out by Pakistan, reaching the deadliest levels since the Taliban seized power of Afghanistan in August 2021. After several days of fighting, Afghanistan and Pakistan agreed to a temporary ceasefire intended to last 48 hours. Though this ceasefire was extended an additional 48 hours on October 17th, it was reported that the truce was broken just hours after the extension as Pakistan allegedly bombed several civilian homes in Paktika Friday evening.

In accordance with agreements made with the original 48-hour ceasefire, Afghanistan and Pakistan officials met over the weekend and agreed to an immediate ceasefire on Sunday, October 19th. Under this agreement, the Taliban said it would not support any groups carrying out attacks against the government of Pakistan, and both sides agreed to refrain from targeting the other’s security forces, civilians, or critical infrastructure.

While the two countries plan to meet again in the coming weeks to discuss a more permanent solution, the prospect of a lasting peace agreement seems unlikely. Without a consensus between Kabul and Islamabad on the very nature of the threat they face, and without coming to an agreement on who the bad actors are, it seems improbable that they can design any coherent, enforceable agreement that both countries would agree with.

Conflict and Recent Escalation

While some sources have reported that the current conflict between the two countries was “triggered after Islamabad demanded that Kabul rein in fighters who had stepped up attacks in Pakistan, saying they operated from havens in Afghanistan”, others claim this is not the cause of the most recent attacks. Instead, the Taliban accused the Pakistan “violating Afghan sovereignty” after a series of strikes in Kabul and Paktika. Islamabad did not formally claim responsibility for these attacks but demanded that the Taliban rein in the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP). Another source reported that the violence ensued following Pakistan carrying out an airstrike against TTP on October 9, 2025. Regardless of the cause of the current conflict, there has been a series of artillery exchanges, cross-border incursions, and drone strikes in the region.

Last week, while a 48-hour truce was agreed upon and later extended pending a meeting in Doha, just hours after the extension, Pakistan allegedly bombed several civilian homes in Paktika province leading to multiple casualties. Pakistan airstrikes also targeted two other locations in Afghanistan on Friday evening. During the initial 48-hour truce, seven Pakistani soldiers were killed in a suicide attack on a Pakistani military camp near the Afghan border. This attack was carried out by terrorists linked to TTP, not by the Taliban. The initial truce brokered between Pakistan and the Taliban government likely did not include a direct agreement between Pakistan and the TTP, so the TTP attack does not technically violate the ceasefire agreement unless the Taliban is proven to have facilitated or sanctioned it. While this may undermine the spirit of the ceasefire and encourage retaliation by Pakistan, it is not a direct violation. However, Islamabad’s attack on civilians in Paktika is in direct violation of the agreement.

Throughout the duration of the current conflict, the Taliban has denied providing haven to armed anti-Pakistan groups and instead accused the Pakistan military of spreading false information about the Taliban sheltering Islamic State fighters in the country. Islamabad has denied these accusations of spreading false information, instead accusing Kabul of granting these armed groups residence inside Afghanistan to wage war against Pakistan with hopes of replacing the current government with a stricter form of Islamic governance.

Despite the disagreements and potential breaking of the truce agreement, the two countries agreed to an immediate ceasefire during Doha talks on Sunday, October 19th. Pakistan’s Defense Minister said that the latest ceasefire meant “terrorism from Afghanistan on Pakistan’s soil will be stopped immediately”. As part of the ceasefire agreement, the two counties agreed to establish mechanism to “consolidate lasting peace and stability between the two countries”. Officials from Afghanistan and Pakistan are set to meet again in Istanbul in the coming weeks.

Historical Context

The relationship between Afghanistan and Pakistan has been delicate since Pakistan’s founding in 1947. The Durand Line, the 1,500 mile long disputed border that separates Afghanistan and Pakistan, was first created by the British in 1893 but has long been disputed by successive Afghan governments. Kabul has never recognized the Durand line as the border, instead claiming the Pashtun territories in Pakistan as part of Afghanistan. In addition, Cold War and post-Soviet era conflicts further hindered the relationship between the countries, as Pakistan supported the mujahideen in Afghanistan during the 1980s. Conversely, Kabul, and even the Taliban regime today, have often backed anti-Pakistan insurgents in the tribal areas.

In 2001, the Pakistan openly supported the U.S.-led fight against the Taliban-backed insurgency in Afghanistan, while at the same time, Taliban leaders were enjoying sanctuary in Pakistan with support from the government. Pakistan has a long history of supporting the Afghan Taliban. Now, Islamabad is accusing the Taliban of giving sanctuary to TTP. The back-and-forth nature of an already fragile relationship has led to pattern of distrust, cross-border conflict, and competing security priorities that reinforce the precariousness of the current border clashes. Between 2014 and 2021, changing dynamics between the countries continued as the former Afghan government was replaced by the Taliban.

Implications for Security in the Region

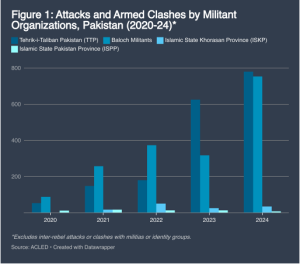

Regardless of who is at fault for causing the current rise in conflict, the renewed tensions between Afghanistan and Pakistan directly impact overall security of South and Central Asia. As border clashes and offensive attacks divert the attention of resources of both governments, militant groups, like the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), may have the opportunity to exploit security gaps. TTP, already strengthened by years of sanctuary in eastern Afghanistan, was ranked in 2025 as the fastest-growing terrorist group in the world, with a 90% increase in deaths linked to its attacks compared to 2024. As a result of this, Pakistan was ranked the second most-affected country by the 2025 Global Terrorism Index, recording its largest one year rise in terrorism related deaths in a decade. Globally, terrorism is on the rise as well. When compared to 2024 data, the number of countries affected my terrorism increased from 58 to 66 this year, with 45 of these country’s conditions deteriorating. TTP will likely reap the benefit of the current cross-border crisis, gaining freedom of movement and filling security gaps along the border.

Meanwhile, Islamic State Khorasan Province (ISKP) and the Baloch insurgency have also positioned themselves to exploit vulnerabilities in the area. 2024 was one of the deadliest years in recent history in Pakistan, with a 70% surge in militant attacks in 2023 and 2025 panning out to be even more deadly. The Baloch insurgency has intensified sharply since the start of 2025, marked by sophisticated attacks and kidnappings. In addition, the insurgency’s “regional spillover, especially into Iran, and competition for resources and prominence among factions of the insurgency further complicate Pakistan’s internal security”, which will only create further opportunity for exploitation by other groups.

Despite not controlling any significant territory, ISKP has expanded its efforts through digital propaganda and strategically orchestrated international attacks. Its use of online infrastructure has significantly enhanced its operational capabilities, making it a formidable transnational threat. While ISKP functioned initially within Afghanistan and Pakistan as an insurgent group, it has since pivoted to a “more flexible and elusive operational model” that is harder to combat. While still maintaining a presence within Afghanistan, ISKP is likely leveraging the current regional instability to expand its operational reach.

The rise in militant violence is further exacerbating the already delicate situation in Pakistan where overlapping governance and geopolitical challenges, like disputes over military operations, continue to raise concern. The U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021 has contributed directly to the resurgence of militant violence.

Strategic and Policy Implications

The escalating conflict and increasing tensions between Afghanistan and Pakistan highlight the need for adaptive security strategies that account for the historical context and the present-day realities of militant violence and conflict along the Durand line. This should be incorporated into a broader, formal peace agreement between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Any sustainable resolution must move beyond temporary ceasefires and reactive operations to establish a structured means for open dialogue, implementation, and mutual accountability. The future peace agreement should incorporate requirements for joint counterterrorism coordination, intelligence sharing, and localized stabilization programs that rebuild trust between the two countries.

But first, the countries must resolve a fundamental point of contention: who qualifies as a terrorist actor? This disagreement lies at the heart of their historical security dilemma. For Islamabad, groups such as the Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan (TTP) represent an existential threat to the state, responsible, especially in 2025, for the some of the deadliest attacks in modern Pakistan. For Kabul, however, the TTP shares ideological and tribal affinities with elements of the Afghan Taliban, and many within Afghanistan view the group as an ally rather than an adversary. Further, the Taliban fear that “coercing the TTP to surrender to Pakistan could incentivize/persuade the group’s leadership to make an alliance with the Islamic State Khorasan, which poses an existential threat” to the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan. Additionally, Afghanistan refuses to recognize the legitimacy of the Durand line.

This asymmetry makes consensus on counterterrorism, and therefore a peace agreement, nearly impossible. Pakistan seeks to neutralize groups challenging its sovereignty and is asking for Afghanistan’s help to do so. However, the Taliban regime shares ties with the same groups Pakistan is looking to eradicate. At least in some respects, the Taliban’s goal of promoting their version of true form of Islamic law aligns with the TTP’s vision of reshaping Pakistan’s secular government. As a result, the two governments are unlikely to come to an agreement that satisfies all of their individual requirements. Addressing this gap must therefore be the first step in any lasting peace agreement. Without this, Pakistan’s counterterrorism operations will continue to be perceived in Kabul as a violation of their sovereignty while Afghanistan’s inaction against the TTP will remain intolerable to Islamabad, ensuring the cycle continues.

Risks and Strategic Outlook

The greatest risk now facing Afghanistan and Pakistan is a strategic impasse originating from disagreements on their fundamental beliefs. Without agreement on these fundamental definitions, neither state can design coherent, enforceable security policies that the other would agree with.

Islamabad maintains that everything hinges on Afghanistan controlling terrorists operating within Afghanistan and that anything coming from Afghanistan will be a direct violation of this agreement. While both sides agree that there needs to be an immediate eradication of terrorism, and while Afghanistan acknowledges terrorism as the main cause of tensions in their current relations, it remains to be seen whether the two countries will actually agree on what the path forward entails. Taliban leaders insist that the TTP is a domestic challenge that Pakistan needs to address. With this dichotomy, it seems any peace agreement will be quickly violated.

The longer this ambiguity persists, the more entrenched groups like TTP, ISKP, and the Baloch insurgency will become, exploiting divisions between Islamabad and Kabul to expand their depth and breadth. Without a reliable agreement that establish shared desires, even a more permanent ceasefire will only offer temporary relief. The enduring risk is not merely renewed conflict, but the institutionalization of instability along one of the world’s most unstable, and disputed, geographic borders.

Policy Options If Afghanistan and Pakistan Agree on a Path Forward

To prevent further destabilization, Afghanistan and Pakistan must first pursue a structured process aimed at definitional alignment and mutual recognition of threats. Any such agreement should be moderated by a group, such as the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, or facilitated by a neutral state such as Qatar. Through either avenue, there are three priorities to establishing a long-term peace agreement:

Ultimately, stability in the region will not emerge from military dominance but from political alignment and mutual agreement. A sustainable peace agreement must integrate adaptive security policies that both countries support, ones that explicitly recognize the diverse ideological and operational profiles of current terrorist and insurgent organizations and those still to come. Only through such a comprehensive approach can both counties reclaim control over their respective border regions and deny transnational militants the opportunity to exploit their divisions.

*image credit: VOA.